Writing code with LLMs (February 2026 edition)

Writing code with LLMs (February 2026 edition)

At the start of the year, I said to Mahhek, a fellow developer "you need to learn how to use these coding agents - because what you and I do will not exist, as a job, by the end of the year".

It turns out I was ten months out.

The 6th of February 2026 was the day when my job changed.

In this last week, I've worked 40-odd hours. I've spent maybe 2 or 3 hours actually writing code - apart from holidays, that's probably the least I've coded in almost thirty years of being a professional software developer. Yet, this past week, I've shipped more working features to production than I have for the rest of the year.

Opus 4.6 is the reason[1]

Last year, I would ask Claude Code to do something. First it would write a plan, which I would look at. Sometimes I would feed back, sometimes I would accept the plan. And then Claude would get to work writing a load of code. And once it was done, I would perform a code review on the pull request it had generated. I would look at the git diffs, I would run the application and check the UI, I would feedback on the code that was written.

However, and I cannot stress this enough, I hate doing code reviews. They're boring, take a lot of mental effort, they take up a lot of time and, did I mention, they're really really boring?

And because of that I would prefer to write the code by hand in the majority of cases.

Opus 4.6 changes this.

Our current priority is a project called Site Manager. This is a Rails application and it's got a high test coverage. But more importantly, it's got Gherkin specifications for all the important features.

Why Gherkin? Because we are specifying the functionality from the point of view of the person operating the system. And I'm writing that specification in (formal) English - instead of starting out by thinking about database tables or data structures or algorithms. I just open a text editor, write out how I think it should work and worry about the implementation later.

Except now I don't need to worry about the implementation.

This week, my workflow has been:

- grab an issue from the queue

- write a Gherkin specification for it (or amend an existing specification)

- fire up Claude Code, select Opus as the model, and switch on "Plan Mode"

I give Claude a prompt that goes something like this:

Look at spec/features/some_functionality.feature - this describes a new feature that we need adding to the system.

Or

Look at spec/features/some_functionality.feature - this describes a change to the existing functionality in the system - you can use

git diffto see how it has changed.

The next part is really important:

I reckon making this change will involve modifying these files - app/models/site.rb, app/models/staff_member.rb, app/models/staff_member_attendance.rb - and will require new end points adding that follow a similar pattern to the existing ones in config/routes.rb and app/controllers/staff_members_controller.rb. Finally we'll also need to amend the admin-only configuration editor at app/controllers/account_configuration_controller.rb and add a Javascript configuration editor - similar to app/javascript/components/configuration/incident_report_editor.js.

Finally:

Read the specification, look at the files and then write a plan for implementing this feature. If you are unsure about anything, or there are potentially multiple ways of proceeding, ask me for advice.

Claude then reads those files and, usually, starts reading a load of related files as well. Then it starts writing out a plan - stopping to ask me questions if it needs to.

This step generally takes a bit of time - up to around ten minutes - and I need to sit and watch what it's doing - both because it might ask me questions, but also because I might need to interrupt it if I think it has missed something important or is heading in the wrong direction.

But when it's done, it presents me with its plan. So far, this is pretty much the same as what I was doing last year.

The difference is that now, Opus 4.6 is so good at code, I can trust it to implement the plan it has written. If I agree with the plan, I will almost certainly agree with the code. With one caveat - I need to be sure that the user interface is correct and matches the patterns used elsewhere in the application.

And this is where using Gherkin specifications helps again.

Gherkin breaks the functionality down into steps. Each step is mapped to ruby code that drives a browser, following links, filling out fields and clicking buttons.

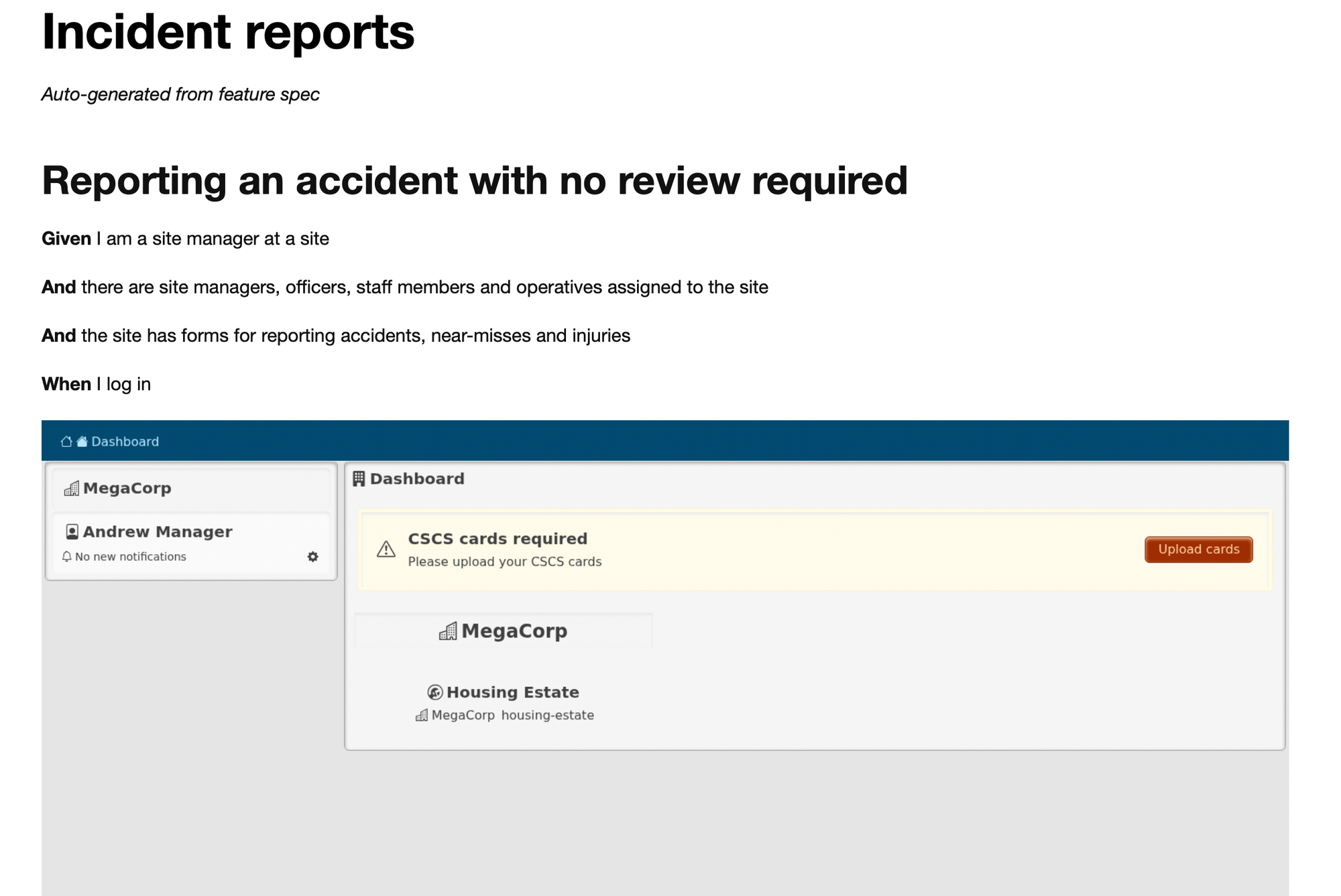

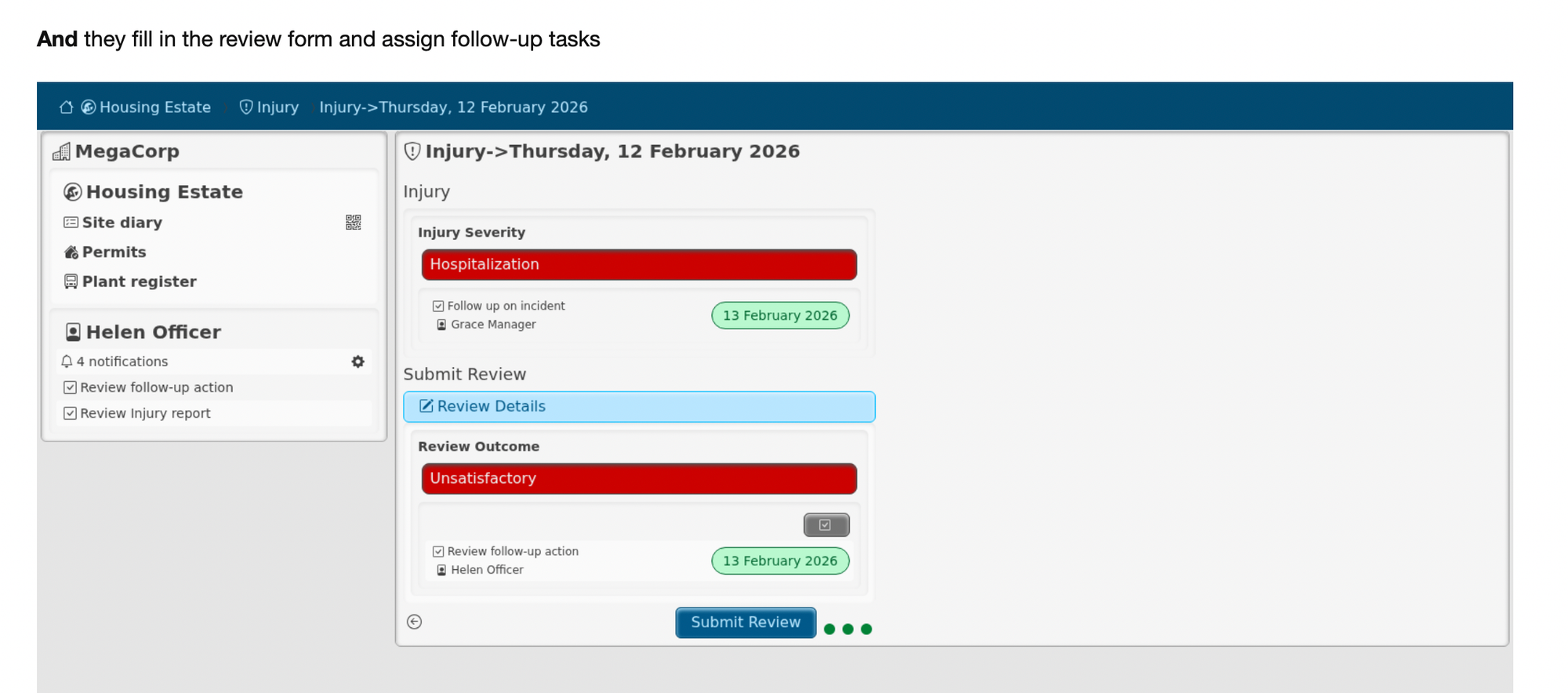

So, inspired by Showboat and Rodney, I've added a hook into each step that saves a screenshot. Turnip (the runtime I'm using for my Gherkin specs) generates a markdown file, with a section for each scenario, then a line for each step, with the screenshot embedded alongside it.

So Claude goes away, writing its code[2], including tests for each thing it does (much more comprehensive that I would do by hand) - and as it runs its specs, checking it hasn't broken anything, I get a document showing exactly how the feature works and what it looks like, step by step.

This makes the code review an absolute breeze.

I just need to have a brief look at the steps file to make sure it's actually testing for the correct outcomes. And then I look at the feature document and make sure that the user interface looks the part.

Once those are done, I know the feature is good enough to ship - so I merge the PR and can move on to the next thing.